Art Therapy Accessibility Issues in the Traumatic Brain Injury Community

Every day, there is more evidence demonstrating the value of art for brain health. While the benefits of art therapy seem straightforward, the reality of pursuing creative activities for a person living with a moderate to severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) is complex.

Every day, there is more evidence demonstrating the value of art for brain health. While the benefits of art therapy seem straightforward, the reality of pursuing creative activities for a person living with a moderate to severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) is complex.

Peter was 18 years of age when he sustained a severe traumatic brain injury. He stayed in hospitals for seven months. When he left inpatient rehab, he couldn’t eat solid food, walk, talk clearly, or control his bladder or bowels. He had short-term memory loss and severe tonality in his arms and legs. The amount of effort it took as his primary caregiver to enable him to participate meaningfully in art was giant. Setting everything up. Helping him stand and balance while painting. Rinsing his brush. Moving the canvas and loading the brush with paint. Then,…cleaning up afterward. The larger the artwork, the more energy and time required. But the rewards were evident from the very beginning. Joy. Satisfaction. Accomplishment. Are there more rewards from an art activity than we knew? Yes.

Because the benefits are real, addressing these issues requires attention from providers and society to truly incorporate art therapy into the long-term TBI journey and ensure the best possible outcome in rehabilitation. How does a brain-injured person handle frustration when their hand and fingers don’t do what they want? How do they work with visual impairments? How can they manage ataxia or tonality? I was able to discuss these hurdles with three other parent-caregivers to illuminate the barriers to art therapy through our eyes.

Benefits of Art Therapy

In a study conducted by Professor Semir Zeki, chair in neuroaesthetics at University College London, fMRIs (Functional magnetic resonance imaging) were used to observe blood flow into the participants’ brains as they were being shown images of paintings by major artists. When people viewed art they considered beautiful, blood flow increased by as much as 10% to the region of the brain associated with pleasure. Cerebral Blood Flow (CBF) is well known to be critical in managing a traumatic brain injury; blood is responsible for oxygen delivery in all body parts. Blood flow is critical in the brain because the brain has enormous oxygen demands in order to function correctly. For its size, the brain uses a lot of oxygen. According to a study of human brain evolution, “In humans, although the brain represents only 2% of total body mass, it consumes an astonishing 20% to 25% of the total body energy budget…” There are many different ways to increase oxygen delivery to the brain, such as cardio exercise and Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy. How amazing is it that research is finding art is not only beneficial for well-being but it has physiological benefits —bringing that much-needed oxygen to the brain!

Barriers to Art Therapy

What abilities are required to participate meaningfully in an art activity? Being able to hold an art tool? The ability to see? Perhaps. The abilities necessary for art depend on the type of art (painting, sculpting, karate, music, writing, yoga, reading) and the level of participation. For example, you might want to play a flute, which requires cognitive resources and sophisticated fine motor skills. Or you can listen to flute music, which requires listening and attention. A traumatically brain-injured individual may find barriers in being able to sustain a long enough breath to play the flute, coordinate their fingers on the keys, or even have the cognitive abilities of attention and memory to enjoy the process.

The challenges to participation in an art activity are in both the physical and mental side of brain injury. Barriers may be short-term or long-term; it depends on the stage of recovery and the extent and location of brain damage sustained. And just as important are the psychological challenges that may present as a patient progresses. Frustration, depression, anxiety, and other mental disorders may make taking part in creative expression complicated. What are some real-life challenges for traumatic brain-injured individuals when considering art therapy?

Three years post-injury, Peter was challenged by fine motor skills while flicking paint onto a watercolor piece he created of a starry gaseous nebula.

Caregiver Discussion

During two video meetings with four different caregiver-parents, we shared the barriers and blessings of incorporating art into rehabilitation and as a long-term activity. There were three core things that we all agreed on:

- There are barriers to this form of therapy in all stages of the brain injury journey.

- Art has an extensive range of real benefits for the traumatically brain injured.

- If accessibility issues were addressed, incorporating creative activities on a regular basis would be valuable and desirable.

The details of each caregiver-survivor experience with art and art therapy really brought to light what providers and caregivers could change to forge better outcomes for the traumatically brain-injured.

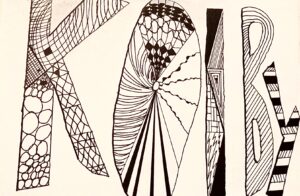

Yvonne’s son, Kobly, has limited physical capabilities. Kolby’s consciousness varies; sometimes, he responds to commands, and sometimes he has trouble following commands. He received little to no art therapy in the hospital and inpatient rehabilitation. Holding a paintbrush, pen, pencil, or other art tool is physically challenging. Adding to the barriers is the fact that, like most TBIs, vision problems prevent Kolby from easily tracking an object (horizontal nystagmus).

Kolby's pre-accident artistic rendering of the letters K, O, L, B, and Y with intricate designs inside each letter to spell his name.

Kolby's drawing of a dog pre-accident.

Picture of Ruff Family (L to R): Kyle, Yvonne (mom), and Kolby. Not pictured: Keith (dad). Taken the year of Kolby's accident.

Wendy’s son, Mike, has vision challenges as well; his depth perception is impacted. He had some art therapy and has attempted art activities a few times with his mother. One eye strays (strabismus). Kolby and Mike are not the only TBI survivors challenged with vision problems following injury. Studies show that an astonishing 90% of traumatic brain injuries result in visual difficulties, according to the Neuro-Optometric Rehabilitation Association with “…TBI patients suffer[ing] from visual dysfunctions such as, but not limited to, blurred vision, sensitivity to light, reading difficulty, headaches with visual tasks, reduction or loss of visual field, and difficulties with eye movements.”

For Mike, who was finishing a degree in art at the University of Vermont when his accident occurred, there is another barrier to participation: psychological. His mom reports that Mike feels frustrated. Mike was used to being able to draw, and now his eyes and hands don’t work the same way. In addition, like many activities for a traumatically brain-injured person, it’s exhausting.

Present-day photo of the Schwartz Family in front of a waterfall (L to R): Fran, Mike, and Wendy

Sock design while Mike worked at his senior internship at Essa Co. Jimi Hendrix socks.

Mike's watercolor of snowy mountains and sky was made before his accident.

Mental and physical fatigue is prevalent for TBI survivors. Amy’s daughter, Sierra, has moments when the amount of energy necessary for her to manage things that we consider “normal daily activities” can drain her to the point of needing a nap. Every activity, including pleasurable ones, requires far greater resources to complete for a person who has suffered a traumatic brain injury.

Maria’s son, Peter, who finds much pleasure in art and pushes himself to watercolor or draw, can fatigue from the exertion involved in getting his hands and fingers to flesh out his artistic idea. Occasionally, frustration can impact his enjoyment. Peter and Sierra both had limited art therapy in the hospital and inpatient rehabilitation, and both continue to practice art expression in their lives and would like to do more.

Meaningful Participation in Art: Removing Barriers

What can be done to assist the caregiver and survivor in pursuing meaningful creative expression? Though physical and psychological barriers abound, all acknowledged that having art as a regular part of the survivor’s life would be valuable. Parent-caregivers in this discussion shared some techniques and tools that helped or might help mitigate some of these obstacles.

- Wendy felt that Mike might be more incentivized by group art activities or having to teach art to others, especially little kids.

- Maria reported that Peter became more active with art when he discovered that a program on his iPad, Adobe Fresco, allowed him to redraw as many times as he liked by clicking a button.

- Yvonne wasn’t sure how art could play a role in Kolby’s life because of the physical barriers he is presently challenged with. Participation in art doesn’t apply to just visual arts. Studies have shown that the pleasure experienced from listening to music, reading, or listening to books…all forms of creativity, can increase the blood flow into the brain.

Some of the challenges with participating in art involve the caregiver's capacities. The time and energy of a caregiver can be consumed by regular life duties, caring for a house and family, possibly juggling work, and, of course, the physical and mental well-being of another person who may require a large amount of care, like dressing, g-tube feedings, driving to appointments, bath-rooming, medicine, preparing meals, etc. How can a caregiver incorporate one more activity in addition to the basic rehabilitative activities such as walking, speech, memory, self-care, etc.?

I recall feeling half amused and half overwhelmed when my son began outpatient therapy and a therapist would provide “homework.” While they know our job is overwhelming as a caregiver, they don’t really know. Health insurance cannot possibly understand how exhausting being a caregiver is. Caregivers need more help; therapists and personal care assistants who are capable of handling rehabilitative work. Many survivors cannot do it for themselves.

For a long time, maybe two years after his accident, Peter participated in his therapy but was not self-directed. He lacked the awareness necessary to take charge of his own rehabilitation. I was that part of his brain. I was his motivating force. And, even after he has gained so much ground, we still need to stay near him for safety when he is working on exercises. Without supervision, he may suffer a secondary brain injury or other injuries, and consequently, the insurance will incur more medical expenses, and the caregiver will be more taxed. We need state programs and insurance to answer the need for more trained support services, more extensive benefits for therapy sessions, and incentives to attract the right people to these jobs.

Meaningful Participation in Art: Unmask the Invisible’s Weighted Paintbrush Project

One physical barrier for many brain-injured persons at some stage of their journey is control of an object. Peter has ataxia, an involuntary movement or shake. He discovered that a weighted pen or pencil helped him control the shake and provided sensory feedback so that he could have more control. Many patients, especially earlier in their journey, experience some level of difficulty with fine motor skills. Not long after Sierra was injured, she suffered a stroke; this left one side of her body difficult to manage, including writing and drawing. Unmask the Invisible is partnering with engineering students at Thayer School of Engineering to create a weighted paintbrush. We aim to create a weighted paintbrush or a small-weight device that attaches to a paintbrush. This will empower a large section of the brain-injured community to participate meaningfully in art therapy.

One of the tasks of this article is to reach further. Not just in physical distance but further into related communities: art communities, brain-injury communities, individual providers, and health organizations. We hope that art has another power: the power to be seen and heard.

Resources to Explore:

https://art4healing.org/reports/special-report-art-and-the-brain/

https://art4healing.org/reports/special-report-mental-health-benefits-expressive-art/

https://acrm.org/rehabilitation-medicine/how-the-brain-is-affected-by-art/

https://noravisionrehab.org/patients-caregivers/about-brain-injuries-vision

What more can we do?

Support Art Therapy

Survivor/ Caregiver Survey

Unmask the Invisible would like to explore the subject of accessibility to art therapy for the traumatically brain-injured by conducting a survey with survivors and/or their caregivers.